Autumn Mist in Mountains and Streams 溪山秋霭图

Yao Lu has crafted a picture of idyllic nature composed from fragmented images of urban construction sites to communicate an urgent issue in China: the aftermath of demolition and relocation caused by the country’s rapid urbanization. Scenes of rubble and debris piled high on city streets next to half-demolished brick walls are so familiar that they have become normalized in China today; Yao’s artwork destabilizes that sense of familiarity by directing our gaze so that, from a distance, the landscape is pure and painterly, and mostly untouched by human presence. Only up close is the image revealed to be a photomontage of rubble and garbage.

Put differently, the pictured landscape is imaginary, perhaps even phantasmagoric, yet real. Ephemeral autumn mists encircle towering mountains, Where the wet air and winding streams meet, there is a seamless passage conveying an ambiance of mystery and ambiguity. A lone pavilion awaits. Life rendered through the humans, temple, and the solitary tree feels smaller and inconsequential compared to the sweeping mountains and rivers. There is something sublime about them.

Focusing more closely, the compositional elements subtly contort to a reality of filth. Even then, it is hard to unsee the beauty. But, in fact, the mountains turn out to be protective netted coverings over collapsed wooden structures (the coverings are used at construction sites to prevent dust, asbestos, and other hazardous materials from rising up into the air). The rubble at the foot of the mountains once was a building marked with the Chinese character chai (拆)—a verb meaning to demolish or dismantle, often painted on buildings planned for demolition, a symbol of the radical transformation of cities. As the most readable symbol on the broken structure, it marks the remains of something unknown, only speculated. A mark of a disappeared history.

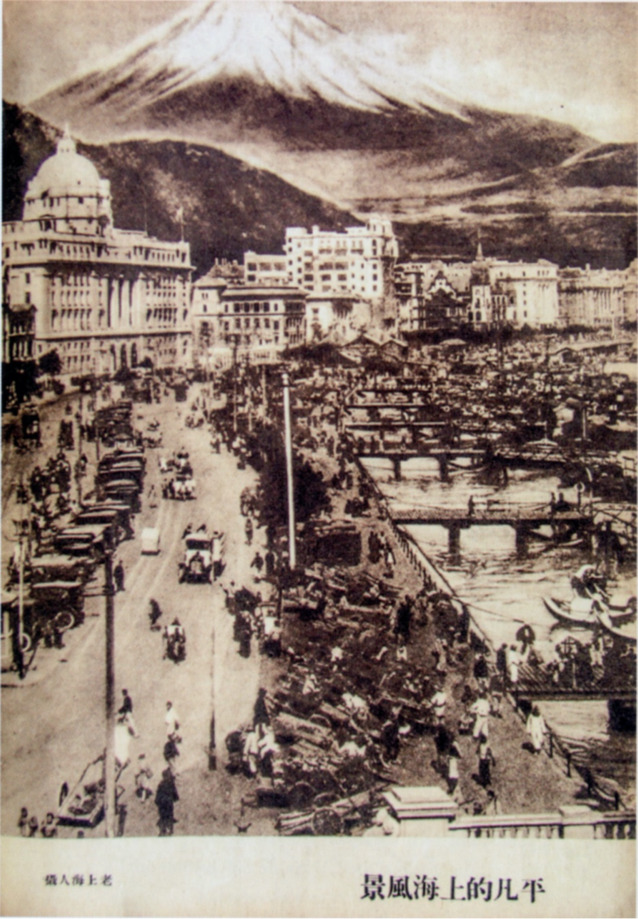

Yao Lu’s photographs often and rightly are compared with twelfth-century Song-dynasty brush-and-ink fan paintings. Their beauty depends upon that comparison, to some extent. But there’s more to them. This particular picture, in dark greys and dirty whites, also has analogues in slick black-and-white photomontages of the modern city featured in 1930s commercial magazines such as Modern Sketch (Shidai manhua 时代漫画) or The Young Companion (Liangyou 良友). Take, for instance, the montage An Ordinary Shanghai Landscape (Pingfan de Shanghai fengjing), where Mount Fuji is the backdrop for the city of Shanghai. The image emanates tensions and destabilization felt from the looming threat of Japanese colonialism. By juxtaposing a national symbol of Japan against the thriving waterfront, the montage embodies shadows of Shanghai’s anxiety that are, in some respects, akin to Yao’s assemblage of debris. Both unveil the psychological discomfort of living within a fragmenting, kaleidoscopic city space.

Yao Lu’s photography practice thus works complexly—through an aesthetic of fragmentation that has long-lived roots in China’s urban visual culture, and a cut-and-paste picturing process that itself can be indexed to the real fragmentation of the cityscape undergoing demolition and construction. By working with “beauty” and cultural essentializations of nature from early history as well, he creates a strange space in his artwork for the viewer to feel estrangement and distance—from the present “normal” cityscape—and from those images of perfected nature from the deep past.

Nicole Chik