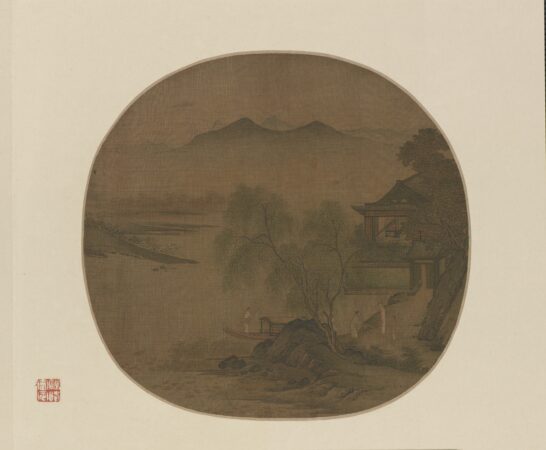

Passing Spring at the Ancient Dock 行春古渡圖

As you move towards Yao Lu’s Passing Spring at the Ancient Dock, a majestic contour of mountains and a meandering river enshrouded in mist floats into view. A fluid sense of depth and distance between you and the landscape is enhanced by the composition of the primary subject—mineral green mountains, ranging in size from foreground to background. The misty river twining around them serves as a gateway to the farthest mountain that recedes behind dense, drifting fog. In the foreground, a solitary boat sits on the riverbank, and three other boats depicted as if miniature drift down the centre of the waterway, creating a picture of tranquility. The interconnection between mountain and water is enhanced by a narrow white waterfall that cascades down a cliff on the right corner of the picture. A solitary pavilion on the top of one mountain reveals humans’ trace in the realm of the spiritual, as the mountain has been regarded as a holy retreat for men in quest of immortality and a pure spirit since ancient times. Passing Spring at the Ancient Dock bears a remarkable resemblance to a Southern Song (1127–1179) blue and green landscape painting—Waiting for the Ferry―in both compositional and poetic setting, and more specifically, the subtle use of mountain, water, and other motifs to create a sense of timeless harmony and beauty.

When you step closer to Yao’s work and attempt to ascertain further details, astonishingly, what you discover is that the landscape is not composed of verdant green mountains, but rather discarded urban construction waste covered by green nylon netting scaled out of proportion. The river in the foreground is represented by uneven and muddy pavement with drying puddles. Four tiny figures wearing yellow helmets, walking at the bottom of the vast “garbage mountain” (lajishan 垃圾山), reveal a human presence in this landscape unexpectedly embellished by trash.

In fact, it is not an idyllic scene like an intimately sized Song fan, but a manipulated photograph composed of images of messy, disordered, and dusty construction sites in Beijing, a by-product of China’s rapid urbanization. Just imagine yourself as the tiny figure standing in front of this massive garbage mountain, or landfill, in reality, where the air is filled with the overpowering stench of decomposing organic waste and toxic, acrid smoke from burning plastic trash on the site: What feelings do you have as you become a part of this “landscape”?

Historical landscape painting is seldom mere artistic depiction of the external world. Rather, it seeks to promote a conceptual perception of nature perfected, designating an ideal world that reflects harmonious unification of all entities. Unexpectedly, Yao visualizes that unsightly waste and beautifies it within an idealized framework of landscape painting. His artwork asks, should we treat waste, which is formed from nature by us, as part of nature—or as nature itself?

Yuzhi Zhou